Snow and temperatures are falling. These poems warn, advise, and console. Beyond that, drive with caution.

Snow Advisory

Across time zones the wind wipes

everything clean

The radio warns of whiteout

on the freeway

cattle spilled from a ditched liner

wander across the passing lane

Then a flicker

a shudder of the fridge

the radio’s dying sigh and

darkness hauls down the last of the day

Outside on the street not a tiremark

not a rooftop retains its shape

no straight line anywhere

beyond this frosted windowframe

No light but from the moon

reflected on snow

no sound but the howl through loosened eaves

the scrape of my fingernails on glass

Colin Morton from The Local Cluster (Pecan Grove Press)

Black Ice

You didn’t see this coming but

there’s no way to back out now

Steer into the skid

look for traction on snow

Don’t lock the brakes or it’s all

gone to smash

Have matches, candles, blankets with you

If you’re stuck in a snow bank

that blocks the exhaust

don’t run the motor for heat

Open the door if you can

Breathe fresh cold air

Look up and be glad

you can see the stars

Colin Morton from Winds and Strings (BuschekBooks)

October’s breath ferments in the lane

fallen apples tomatoes on the windowsills

& everything’s new again even first things

even bird cry the whitecaps’ swell and lap

our first winter together leaves

blowing our questions scattered at our feet

half-familiar faces slips of paper reminders

stuck between pages found years later

urgent voices in sleepless houses (remember?)

our faces as they once were bright in the darkness

we walked each other partway home partway back reluctant

to give up the dead weight of night

the sweet weariness in our limbs our words

too late our shadows new as ever.

-Colin Morton, from Coastlines of the Archipelago

Our gardens continue to bloom and produce food. While they do, here is a haibun series in celebration. It’s from my Pecan Grove Press book The Local Cluster. As always, the way to receive this book tax and postage free is directly from the poet: colinmorton550@gmail.com $15.

Hortus Urbanus / City Garden

Twice now this morning I am wakened by full-throated geese Veeing over my roof. How is a poet to dream through this?

High in the wind-torn pine a cardinal pipes his claim to all he surveys. From chimney top the crow replies sharply. In cedar branches sparrows watch a blue jay splash in the water.

Fleet light, how do you

taste? How have you left no tracks

in reaching this place?

~

I pay in silver for bags of earth to level the ground round the roots of a thirsty shade tree deep in the intricate heart of a city at the confluence of three rivers where once was forest and swamp.

The scene calls for Kurosawa’s camera and patience, for a narrator if you must: a wolf. Or the spirit of a wolf, who once would have kept down the raccoons who rattle my garbage cans at night. One who stares back, unafraid of my bluff.

Bats in the branches. O, and the moon is full. Already, I think, then remember how long it must be since I looked up at night and caught in the corner of my eye a fleeting wing.

A sound in the garden

— fallen branch or door slammed —

then silence recomposing around it.

~

In this garden, maple is a weed. It infiltrates from melting snow like stick insects about to take wing. Then the yellow parachutes descend, and soon whirlybirds everywhere, scattering.

In the splash line under the eaves, out of street sweepings, in the crack between pavement and foundation, the maple keys grow. Sometimes a sapling wedged between rocks against the fence reaches shoulder height before I find and uproot it.

It’s a game of stealth. Given time and neglect it would bring my house down. I bend and tug.

I know this isn’t nature, or

I would live in a grove not an avenue.

My life’s as forced as a hybrid rose.

~

Don’t suppose the garden’s a silent refuge. In the ice storm, a tree fell across the street and for two weeks no buses ran. No rush hour. All but rescue crews stayed home. Then silence encased the city, shattered only by falling ice, the moan of tree trunks bent low.

With fine weather construction crews return. They clear debris, knock down walls, drive fenceposts, dig foundations. The ball-capped wood-tappers emerge from their dwellings with power saws. Then there’s the sawing of mosquitoes.

This isn’t what the magazine headlines mean bythe poetry of the garden. If you want to escape the grind, the neighbours’ deck at semester’s end with canvas chairs, radio and a cooler full of beer serves as well and better.

Down here in the dirt, it’s real

dung beetle country:

the greatest shit of all time

without commercial interruption.

~

With a fork like this my grandfather stacked five hundred bails before noon, then sat on the last and open his Thermos, ate sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper, and counted his herd’s winter feed against next spring’s likely price for beef on the hoof. In an hour my hands blister, turning compost rank with corruption, which next summer will midwife sweet drafts of lilac, peony, lily on the breeze.

What chemistry! with Whitman I exult. That the winds are not really infectious … That the cool drink from the well tastes so good. Yet I filter my water again, through charcoal, as I moderate my vices, read labels as if avoiding what kills will save me.

Over the slimy stew of roots and leaves I spread ash from the fire, bone meal, dry stalks, dead-headed flowers. Death’s dominion’s reduced to this little black box, the size of the Arc of the Covenant.

From nothing: this!

From something destroyed: this!

and this! and this!

~

Here before Noah lay strata of ice.

Then for a thousand years, sea bottom. Till glacial runoff carried down a moraine that trapped a freshwater lake. Which turned back to ocean a thousand years later when the tide broke through again, finally retreating as, unburdened of ice, the porous land rose.

Beneath my spade I discover trilobites and bottle caps, no shards or arrowheads, more crushed rock than soil.

The wing of the bee

in its figure-eight beat: O

lead me to the goods.

~

With bleach and brush I scrub algae from the lime-rich bottom of the birth bath. I drain and rinse, then refill for the neighbourhood sparrows and chickadees who gather at the gushing sound. And for the blue jay, who loudly announces his arrival, pauses on an overhanging branch and then, unchallenged, drops to the laurel-wreathed concrete rim. Ostentatiously he sips, sips again, then wades in till his long blue tailfeathers drip. Here he squats and beats his wings, spraying the ground beneath.

There follow the dodgier finches that approach in small, skittish steps, aborted landings. Sparrows skim in low to the ground, sans scruples over drinking another’s bath water.

Soon I will have to scrub again, drain the fertile water over parched lilies, drooping peonies and sprawling poppies—the overabundance that reigns so briefly after months of desert grey and struggling bud. Now rather than feed and coax must the gardener split and spread new growth, swap or bequest or abandon the unstoppable violets.

A small pool contains

— like an open eye —

the world and all.

~

On his northern journey, haiku master Basho saw the split-trunk pine of Takekuma celebrated in ancient verse, though of its fall into the river, too, he knew from not-quite-so-ancient verse.

Many times fallen and replanted, the tree always grew with a split, like the first, thanks to a slip of the woodsman’s ax.

For myself, I undertake no pilgrimage but remain year after year under the same white pine. Wind-riven, spare and lean, a tree of the northern wild with roots twisting deep into limestone beneath a handful of earth.

A few brush strokes on vellum:

craggy historian, lone

pine bent by the wind.

~

Whatever mulching or moving of earth we yesterday left undone may remain now in whatever state we left it until spring. The birdbath’s concrete laurel leaves hold a loaf of snow that will rise and fall with winter’s storms and thaws.

Squirrels chase each other through the cedar, scrap over a cache of food high in the branches of the birch.

One fall day, after digging stones from the garden soil, I set two on end, another across them like Stonehenge, a limestone wedge on top: a mannikin’s head, inukshuk, Herm, a pet who needs no care, who stands out in the windswept snow whenever I look from the window.

Dried flower heads above the snow

— crow and chickadee

eye each other silently.

~

Wintering over: bulbs in deep slumber; roots’ icy nooses; snug branches under yellowed leaves, heaped up around the rose, whose thorny canes slowly mulch them in the drying wind.

Green tendrils hang around the double-glazed window. Steam writhes against the cold pane, turns back on itself like bonsai, barely rising from the teapot’s spout.

On the table beside the tray: the open pages of a glossy garden magazine, a chewed pencil stub, the order form torn from a seed catalogue.

Rose red setting sun

skates the horizon southward.

The windowsill cat

flexes her claws in a dream.

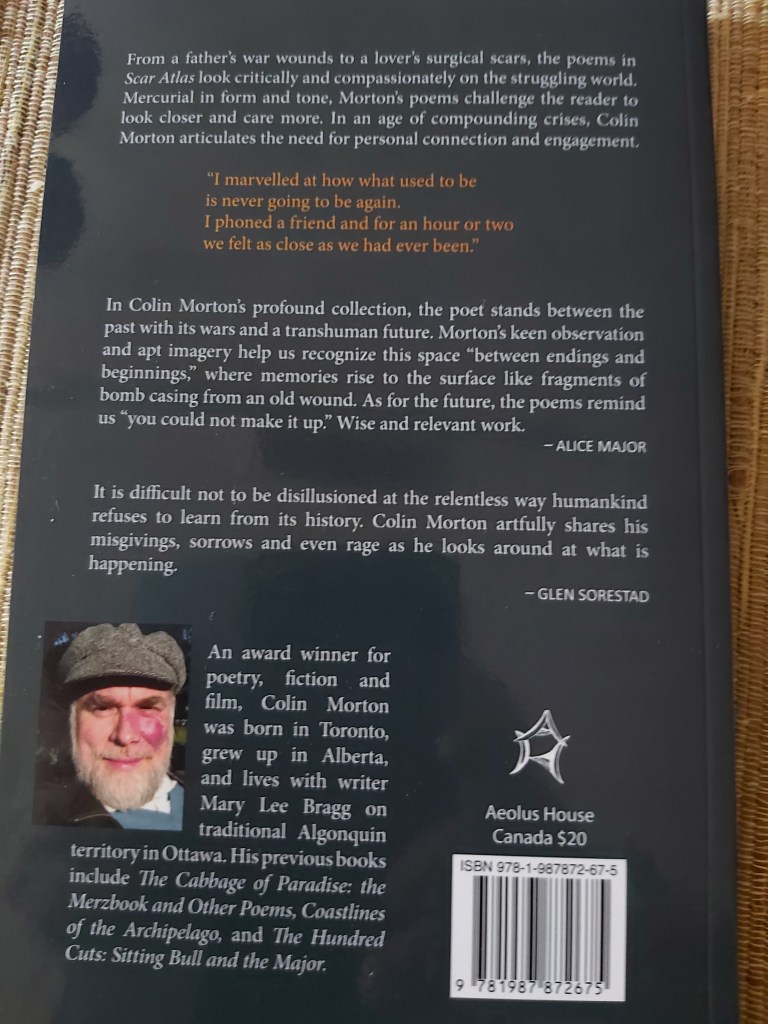

Colin Morton’s 2024 book Scar Atlas is one of ten books by established Canadian poets long-listed for the prestigious Al and Eurithe Purdy award. The $10,000 prize winner will be announced in April, so you have time to read them all. One way to receive Scar Atlas by mail is to email me directly at colinmorton550@gmail.com. The ten books in contention for the prize are:

Read more about the Purdy award at Quill and Quire: https://quillandquire.com/omni/al-eurithe-purdy-poetry-prize-longlist-for-2025-announced/

You can also find a review of Scar Atlas in Devour magazine online.

Some poems in Scar Atlas were written on beautiful Vancouver Island. Even its beauty made me think about have everything perishes.

On the Strait of Juan de Fuca

Walking shorelines under battered

beach house patios, we wonder how

far we would have to run from a tsunami,

how many of these glass walls would hold.

From the top of our climb we see mapped out

the geographic pinch we’re in

where a wave has nowhere to go

but up these placid streets. We’d learn

who said their prayers … whose SUV could float …

On our walk between rows of blooming trees

we imagine the end of it all, as if it’s seasoning,

the salty drop we need to call this love.

Colin Morton

colinmorton550@colintmorton

Introducing the new book of poetry by Colin Morton. Scar Atlas opens with reflections on the compounding crises of our century and ends with memories of the pandemic. In between are two personal sequences exploring the scars life leaves and the healing they represent. Order directly from colinmorton550@gmail.com and pay no tax or shipping: $20.

It is still poetry month, and it is time to acknowledge that, while poems may seem small and inconsequential, they do play a part in making us human.

The Poems

The poems are always with us:

nursery rhymes we sang when young;

jingles for products we never tasted;

lyrics we can’t get our of our heads;

poems we wrote when miserable,

that still remind us how much love can hurt.

The poems stay with us when the pain is gone,

and the memory of pain is sweet;

remain when the names of old friends take flight,

when it is late and we don’t want to go to bed.

The poems tell something they didn’t

last time we read them,

and that makes us want

to discover them again.

Colin Morton

Here’s to new discoveries, all year round.

The Peruvian literary site Santa Rabia Poetry features five of my poems in English with Spanish translations by Colombian poet Maria Del Castillo Sucerquia. The set is called Scar Atlas.

Scar Atlas

My father leaned over the sink

to study his face in the mirror.

With a sterilized needle he probed,

prodded, nudged out a sliver

of bomb casing risen to the surface

years after he came home from war.

Field doctors had removed the larger bits,

phosphorus that glowed in the dark,

then smoothed on a sheet of skin

borrowed from his body lower down,

and when the patient regained his sight,

sent him back to the battle.

As he lay on the sofa watching TV,

his legs thrown across my lap, I traced

a route with my fingers on the map

of shrapnel scars that pitted his shins.

He watched in silence the scenes of war

staged as heroics on the small screen,

never spoke of his own, said only

that the scars no longer hurt.

Now in its 51st year of publication, West Coast literary magazine Event gave me a boost by publishing me with “six new poets” in the 1970s. I am just as pleased to be published by Event in 2023. Here are the new poems, which revisit my post-war Calgary upbringing and that time someone in England published my poems as his own. The first is a prose poem.

Arriving Late

I don’t remember what movie we saw or whether it played at the Capitol or Palace, only that my sister and I arrived late, walked in partway, and stayed for the next showing. When we reached the scene where we came in, I was ready to go but she wouldn’t leave. So I stood by myself at the bus stop downtown on a Saturday afternoon, 1959.

I couldn’t tell how old the man was, the one I’d learn to call a drunk. Shaky on his feet, he squatted beside me on the sidewalk, staring into my eyes, almost crying. He put his arms on my waist and asked me to hold him, so I reached out.

Next thing, a uniform stooped over me,. A second cop pulled the man up by the collar of his dirty coat, asking me if I knew him and did he hurt me. Frightened now, but innocent, I shook my head. More questions followed, but what stayed in my mind ‒ what I talked about later ‒ was my ride home in a police cruiser, radar on the dash, siren wailing when we stopped a speeding motorcycle.

These memories have stayed with me ever since, specific and unchanging. But something is missing from the story, something everyone else could see but I could not: the blood-red birthmark splashed across my face.

Of course the police had to check, but maybe the man on the sidewalk was no molester but the one passer-by who looked at me and cared. Run in for a show of kindness. Maybe he was a war vet, as all men seemed to be, and the sight of me brought him flashbacks of ruined towns, crying children.

I didn’t wonder about any of this then, nor afterward for many years. My memories, if fragmentary, were secure. It was the summer a neighbour’s new Edsel parked in front of our house, and when the squad car pulled up behind it, our front door stood open. My sister called out that I was late for supper, but cobs of corn were boiling on the stove.

Sunday Afternoons

Sunday afternoons my father sometimes slept till five,

weary from a week of work.

Weary too from his year at the front

of the war that defined our world.

A survivor, one of the victors, he earned his rest.

Other Sundays he would lie fully clothed on his bed

and smoke. If I passed the door he would call me,

have me lie down beside him. In silence

we lay, his arm around my shoulder, breathing slow.

I inhaled when he inhaled, exhaled when he did,

trying not to breathe his smoke.

For a few moments, a meditation, we breathed together

and after the time it might take to fall asleep

I would rise and quietly leave him

smoking, perhaps remembering.

Regalia

One week in summer, disinherited tribes

were allowed to camp as their ancestors did

where the Bow and Elbow rivers meet

and wear regalia for once-banned rituals.

Inside the stockade of Stampede grounds

we watched in awe as boys our age

arrayed in feathers and coloured beads

stamped and whirled to pounding drums

near the arena where, last winter,

between periods of a hockey game,

we Scouts performed the Musical Ride

on skates, weaving patterns on the ice.

Clumsy black costumes hung from our shoulders

like bumper cars with wooden horses’ heads,

but our privilege fit so well

we hardly knew we wore it.

Avatars

When my poems resurfaced

under another man’s name

I found second selves in cyberspace.

In the midst of a bull market …

I ran the table …

scored from mid-field …

spent a night with the Stones …

between campaigns for Palestine …

Then these chilling words.

Last seen wading into the ocean

in boxer shorts on Christmas Eve …

On site after site the headlines read

Local man missing, feared dead.